Close your eyes and picture a dragon. Don’t think about it much. What do you see?

Now, a bigger question: Where does that image come from? What unique combination of books and movies and TV and game and stories put that particular dragon in your head?

When I asked myself this question, the first dragon to pop into my head was, annoyingly, one of those behemoths from House of the Dragon, which are more like giant wyverns. This led me to the beloved wyverary (half wyvern, half library) A-Through-L, from Catherynne M. Valente’s Fairyland books. A-Though-L is red, and perfectly drawn by Ana Juan, which made my memory skip back much further, to a tangle of images my brain has labeled “Smaug,” none of which are Tolkien’s original drawing, which was not red.

It’s just that so many other Smaugs I’ve seen were red, so I’ve mashed them all up.

Where do your dragons come from?

When I was small, my dragons came from Mercer Mayer. (Let us not speak of the Sleeping Beauty dragon, which terrified me.) There is no two ways about this: I was a shy child, and one of the books I remember best from childhood is Mayer’s Herbert the Timid Dragon, which features a shy dragon whose attempt to rescue a princess is woefully misunderstood. And one of the books I remember least lingers in my memory because of its perfect title.

Everyone Knows What a Dragon Looks Like was written by Jay Williams, and illustrated by Mayer in a style very different from his Little Critters. I haven’t seen a copy of the book in decades—it may not hold up!—but the title pops into my head whenever there’s a conversation (or an argument) about what “everyone” knows. When I was small, the story seemed to be about imagination, and about knowing that you don’t know everything. But it’s also about not making assumptions about shared knowledge, about not presuming that what you know is the only way to know something. Foolish characters throughout the story assert that of course they know what a dragon looks like.

They’re wrong, of course.

But fantasy fans—and fantasy authors—have very specific, and very personal, ideas about what the dragons in our heads look like. I would bet a small amount of money that an entire era of imagined dragons was influenced by Michael Whelan, with his iconic covers for ’80s and ’90s novels including Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series. Those were not my dragons—too muscular, too dinosaur-like—but they were striking, influential, timeless in a way. There were very different Whelan dragons on Melanie Rawn’s Dragon Prince books, and a memorably sharp-edged Morkeleb for Barbara Hambly’s Dragonsbane, and between all of these covers and more dragons began, for me, to take on more shapes and details.

Some stories have one kind of dragon; some have many. The movie How to Train Your Dragon offered a veritable explosion of dragons—big, small, slim, chunky, in every color and shape. I could not, prior to having seen that movie, have even begun to guess how many different dragons a person might imagine. I was stuck on Smaug-like dragons, or what I imagined Smaug-like dragons to be: large, regal, terrifying and, ultimately, fairly lizard-like, when all is said and done.

Now, I would like to say I have a very elegant and refined and carefully considered idea about dragons. They aren’t too lizardlike nor too catlike; their scales are sleek, their eyes expressive; they are neither good nor evil, but unreadable, maybe wise, maybe just strange. Long heads, elegant necks. Not inherently vicious, though certainly terrifying if threatened. I hate when dragons seem always enraged. It seems exhausting. Haven’t they got better things to do?

Buy the Book

Witch King

But I would like to be surprised by dragons. I would like to see something different than the way they are shown on screen, these days: all glower and fangs and hunger, all browns and dull reds, meant to intimidate rather than to awe. I don’t care whether dragons are aerodynamic or whether gravity says they could fly or not; they’re magic, and they can be as magic and irrational as they like.

In Rachel Hartman’s novels, dragons can take human form, and the main character of Seraphina is half dragon; in Robin Hobb’s world, dragons begin life as sea serpents. I couldn’t tell you exactly what any of them look like, though my mind wants to conjure up dragons borrowed from other artists, other sources. None of them are Falkor, the luck dragon from Neverending Story; none of them are the elegant dragon from Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings.

None of them are the dragons from The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, either—but these video game dragons are the ones I think of when I consider dragons and awe. Glowing, ethereal, massive, dangerous and yet essentially benevolent (they don’t mind at all when you shoot off their scales in order to upgrade your armor), they float, twisting, through the sky above Hyrule. And even on my third playthrough, I stop, every time one soars overhead, and make Link look up in wonder until they pass.

What do your dragons look like? Where do they come from?

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.

Tolkien’s painting of Smaug in The Hobbit is a fiery red-gold.

Smaug–there is always Smaug. Because he’s my first-ever dragon encounter, and still in my view the best. Not quite in second place, but certainly up there in the Top 5 is Eustace Scrubb as dragon, which I think is the single best creation of the Narnia films, without question. And possibly Lewis’ greatest stroke of genius both within the series and outside of it.

However, my dragons will always always ALWAYS be Saphira, Thorn, and Glaedr. Because no one writes dragons like Paolini. He loves them the way dog people love dogs or cat people love cats. That affection rubs off on the reader, and I’m super excited to get more Thorn later this year!

@1 – I thought so, and then convinced myself otherwise! Memory is a tricky thing (and the internet is sometimes not great at corroborating).

Vermithrax from Dragonslayer. A fairy tale that deconstructs and then reconstructs back into what I call a “realistic fairy tale” and with the best and baddest take on a dragon in any film.

For British folks most people will have encountered ‘Y Ddraig Goch’ early on and, once we moved to colour TV, there’s Idris who lived into Ivor the Engine’s firebox for a while.

“Dragon is a big fire-breathing scaly thing that flies” is a concept that goes back, I think, to Beowulf. Chinese dragons fly but don’t breathe fire; biblical and ancient-world dragons (like Fafnir) are just very large serpents; there are plenty of chimaeric creatures in cultures all over the world which are scaly and fly, but, again, no fire-breathing.

The Dragon of Og by Rumer Godden and the Trina Schart Hyman illustrated St. George and the Dragon were my introduction as a toddler. When I was six, my brother got Dragons of Autumn Twilight with the Larry Elmore artwork. Those three dragons gave me Smaug when I got the Hobbit and Lord of the Rings from my uncle as a Christmas gift when I was eleven. Smaug was red for me not ever seeing Tolkien’s original art of Smaug.

As with others, Tolkien’s own depictions of Smaug. My father loves the book, and read it to me regularly as a small child. There might have been a depiction of a dragon passing through my vision previously, but Smaug was absolutely the first dragon character. As I grew older, a explored more fantasy literature and then RPGs on my own, dragons that weren’t “Smaug-like” bothered me, as some part of my brain insisted they were wrong.

My dragons are quite serpent-ish, with wings, and are “lizard-like” only insofar as they have four legs with claws. They’re not brontosaurs or plesiosaurs – they’re dragons! Even the marvelously-voiced Rankin-Bass Smaug suffered from being far too tubby to be a proper dragon, especially when in flight. (Overall, he’s a little too cat-like for my tastes as well, though a little cat in my dragons doesn’t bother me, it ought to be more behavioral than an obvious part of their physiognomy.)

They can be whatever color they are. Smaug himself is obviously the red-gold he’s depicted as, but the very fact that his color is (sometimes) part of his name eventually seemed to imply to me that dragon colors varied, like the rainbow. (That I encountered exactly that in D&D a few years later both cemented the idea and was one more connection I made with the game – although connecting a dragon’s color invariably to its nature is something I’ve always rejected, more than once to my players’ great dismay.)

Orm Embar ftw :) Honorable mention: Yevaud…

I grew up listening to Peter, Paul, and Mary’s Puff the Magic Dragon. And at least once a month Pete’s Dragon was on Sunday afternoon TV, so that was my first image, a friendly almost cartoony dragon. Then my dad read me The Hobbit and introduced me to Smaug and since then that has been my sorta default dragon creature. But I’m also a Wheel of Time reader, and in that The Dragon was a person, but almost more an idea, to be feared but also the savior of the world, and I like that idea best!

@@@@@ 9. zdrakec: Yevaud, “honorable mention”? How DARE you? Yevaud/Mr. Underhill FOR THE WIN!!!!!!!!!!

;-)

Smaug takes priority for me now, due to my love of Tolkien, but I think maybe my first dragon was the Reluctant Dragon Disney cartoon. I can still sing his theme song!

One of my favorite dragons is Maynard Long, R. A. MacAvoy’s titular Black Dragon.

There’s a kind of pedantic character lurking around comment threads like this who’ll insist a dragon must have four legs and two wings, otherwise it’s really a wyvern, a wyrm, a drake, a dragonoid, or some such thing. This is mistake. The concept of a dragon long predates the four legged variety, which originates only in late Medieval European art, and became standardized only through modern pop culture. Myself, I prefer the two legs/ two wings variety. To me, they appear much more convincing, like something that might have actually evolved. And I’ll be damned before I call them wyverns.

As in indelible image, absolutely the Elizabeth Malczynski Dragonsong, Dragonsinger, and Dragondrums covers.

Shout out to H.R. Pufnstuff (although dragon would not have been my first guess) and Puff.

More recently, Todd Lockwood’s renderings for Marie Brennan’s Lady Trent series, as well as Haku from Spirited Away.

(And for your amusement, the Simplicity pattern for a shoulder dragon has in its directions, “Put it together until it looks like a dragon.”)

This discussion makes me think of the dragon pet sim <a href=”https://www1.flightrising.com/”>Flight Rising</a>, which (as of yesterday) has 21 different breeds of dragon; I imagine it must be quite the challenge to keep coming up with designs that are different enough from each other, but are recognizably dragons. (This one has bug wings! This one has a mane and fur! This one has… okay also a mane and fur, but also big antlers!)

Draco from DRAGONHEART deserves mention as a spot-on dragon of the more benevolent sort (with such a beautiful speaking voice and a fine cinematic feature to back him up).

In a nutshell dragons are winged, magnificent and articulate but most definitely not human: they are an elemental power and beast of immense potency, not quite a demigod but far too powerful for comfort (“A joy to their friends and a terror to their enemies” seems as appropriate a summation as any).

The plush dragons on the cover of my favourite copy of Brother to Dragons, Companion to Owls. (Betwixt and Between are a rubber two-headed dragon in the text itself, but plush on the cover image.)

Also the titular Book Dragon.

Excellent books, both of them, though I’m blanking on both author’s names at the moment.

Raphael (1506) and Rubens (1605) depict the dragon slain by St George as a serpent like creature (Garden of Eden) with four limbs and wings. Dark in color and the size of a big pig. Something killable from horseback with a lance. Many gothic cathedrals including Notre Dame have this depiction in stained glass. Tolkien (and Lewis) surely knew about these depictions of dragons. The search for the prototypical dragon must go much further back.

The salient features of the western dragon have been present for 7000 years. When you see a dragon image as a young person you don’t so much learn what that is as recognize it as a dragon. the image is so pervasive there was never a memorable time you did not know what that is. it truly is something that everybody knows like that the ski is blue.

@14 – To me, drake = dragon; the words are doubles, and Tolkien used the words interchangeably. In his LotR appendices, he refers to cold-drakes and fire-drakes arising in the North during the 3rd Age, and that Smaug was originally one of the latter. I’ve always thought of wyrm as a synonym and as an archaic spelling of worm; I now have the notion that if you were to call a dragon a worm to their face you’d be insulting them, however, and the usage of that word in medieval sources seems to confirm that.

(I wonder if Le Guin’s naming a dragon Orm was informed by the word “worm”?)

Other than Puff, the Prof’s dragons are among the earliest I encountered that I remember. My earliest conceptions were flighted, with the number of non-wing limbs (2 vs. 4) not set.

I later learned that some, such as the Chinese/East Asian version, may not be winged; but that type are also depicted as shapeshifters, so their mileage did vary.

Later I encountered Le Guin’s dragons, which are certainly winged. My image of the Pern version is definitely informed by those Whelan covers. And back to Tolkien; when the Silmarillion came out, I encountered mention of both winged and unwinged varieties. Ancalagon the Black is referred to as the first of the winged beasts. Turin’s bane Glaurung has four limbs, no wings, and his movements are frequently described as snake-like; he’s also referred to as the Father of Dragons, so that all the rest of the breed, winged and unwinged, are his descendants.

The dragons of Tolkien and from older Dungeons & Dragons set the standard for me, but I’ve enjoyed seeing so many different incarnations across the years. One enduring favorite was Michael Whalen’s cover for Dragonsbane:

I think my earliest conceptions of dragons come from Anne McCaffery books, which Mom read; the animated Pete’s Dragon; and the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual. So I probably don’t have one default image in my head but at least a couple, from a cartoony version with a rather uniform hide — kind-of like a winged version of Flintstones pet Dino — to a menacing treasure-hoarder with gleaming scales. I must have come across dragons early in my comic-book reading too, yet no specific examples spring to mind.

There’s a kind of pedantic character lurking around comment threads like this who’ll insist a dragon must have four legs and two wings, otherwise it’s really a wyvern, a wyrm, a drake, a dragonoid, or some such thing. This is mistake

This is downright heraldrophobia, and I’m not having it. Weird pedantic obsession with the details of imaginary animals has been our bread and butter for centuries. Take away our dragon/wyvern distinction and you’ll want to deprive us of fire-breathing panthers, tygers, alerions and martlets next. Enough!

Yours sincerely

Croissant Rouge Pursuivant

@20Richard Hall, I doubt that ancient Greeks or Romans, for example, restricted their conception of dragons to the winged quadruped model. I thought I remember reading somewhere that the motif only dates back to about the thirteenth century. I’m happy to be proven wrong, if someone wants to show me older art depicting dragons with those specific attributes. I agree that dragons have always been envisioned with certain salient characteristics, such as serpentine forms and poisonous or fiery breath, but I don’t think our modern genre fantasy novel versions can claim to monopolize the concept.

@21markvolund, I think my online interlocutors insisted that a drake had no wings, but otherwise resembled a dragon. A wyrm, according to them, resembled a dragon with neither wings nor limbs. It must have been on this site that we debated, but I’m too lazy to scroll back through the record to verify the details. I believe you are correct about the interchangeability of these terms in Tolkien, and the origin of Le Guin’s “Orm.” I think “Orm” means snake in the Scandinavian languages.

@24ajay, Your rejoinder is so charming that I surrender. I solemnly resolve I will never again involve myself in an online debate about the fine points of distinction between dragons, wyverns, and wyrms. Let the pedants have their candy.

My perception of what a dragon looks like was forever set by the animated Hobbit. Specifically, the speech that begins with “I–AMM–SMAUUUUG!” Unfortunately the biggest sound effects somehow dropped out when the movie was digitized, but the visuals are still amazing. I got to see a 15mm projection version with big fabric-fronted speakers at school.

And then there’s Ogden Nash’s Custard, the cowardly dragon, who came through when it counted.

I don’t see anything, because the ability to picture things in your head isn’t universal and I don’t have it.

But the dragon I think of when told to think of a dragon is Idris from Ivor the Engine.

(“Do you know ‘Land of my Fathers’?” They’re a Welsh choir, boyo, of course they know ‘Land of my Fathers’…)

Something I’ve been curious about is where/when dragons became very large beasts. As note above, the early medieval dragons seem to be no larger than the horse St. George is riding, and sometimes quite a bit smaller, perhaps related to devils being depicted as smaller than the saint or angel fighting with them. Then by the mid-20th century they seem to be more commonly imagined as larger than elephants – due to popular images of brontosauri, maybe?

I remember an oddly-fascinating book about cryptids and searching for lake monsters with a wierd yet plausible take on dragons and lake monsters being an oversized variant on some very tiny water creature (but I forget which critter, as well as the title, apologies!)

@29 – The Chinese/East Asian conception of dragons does differ from the Western conception, and some of them seem to be somewhat larger, from a little to a lot. Fossilized dinosaur bones unearthed in central and western China for centuries (and sometimes ground up and used in traditional medicine) were considered “dragon bones.”

In Western folk tradition, they do seem to have not been so large that they couldn’t be killed by small groups or even by a hero acting alone. There is charging it with a lance, as St. George is supposed to have done; stabbing it in its belly from a ditch while it slithers overhead, the method in use both by Turin against Glaurung and by Sigurd against Fafnir, the latter being the inspiration for the former; or tag teaming it like Beowulf and Wiglaf.

Tolkien’s dragons did get bigger; Smaug could not be slain by the Dwarves acting in concert (although he did have the advantage of surprise in his attack against them), but he was taken down by the proverbial lucky shot.

My first dragon would have had to be from D n D (not the advanced version). but the first *image* I remember is from my first NorWesCon (#3, I think) and local science fiction convention. The original Michael Whelan painting for the cover of The White Dragon was on display – it’s about 3 feet across. That’s a dragon that I remember.

Of course, sometimes a dragon can be…lucky

[and have fur!]

British, and we know what a dragon looks like from the flag.

The Lambton Worm (“worm” and “orm” are just English and Scandinavian words for serpent or dragon) could wrap itself “ten times roond Penshaw Hill”.

side note: Gríma Wormtongue is not supposed to have a yucky tongue like a slimy annelid, but to have speech as clever as a dragon’s. “Silvertongue” would be a modern analogue.

For me, the most memorable early depiction of a dragon that I read was the description of Orm Embar from Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Farthest Shore. I first read it at least forty years ago, and have not read the book in several years, but I can still recall bits of the passage by heart.

I encountered Tolkien’s Smaug, C.S. Lewis’ Eustace-as-a-dragon, and probably Puff the Magic Dragon earlier (around the age of eight), and Anne McCaffrey’s dragons and fire lizards, as well as the multi-colored dragons of 1st edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, at about the same time (around age ten), but it was Orm Embar and Kalessin that struck me most.

My first impression of McCaffrey dragons of Pern was definitely not Michael Whelan’s art, but the cover illustrations for the Harper Hall trilogy by Elizabeth Malczynski, with their delicate, ornate fire lizards (as cited by @15/WMc above). When I subsequently encountered Whelan’s covers, it took me some time to get used to them.

I have long found East Asian dragons fascinating, and would like to learn more about them, but when I think the word “dragon,” the “Western” image of a dragon is still what comes first to mind.

Two dragons loom large from my youth, and they couldn’t look less alkie.

The first is the cat-like Smaug from the 1977 Hobbit cartoon. I still love that depiction. Dragons are, after all, pretty catlike in their desire to take long naps on top of their horded gold.

The second is the dragon from Dragonslayer, which my parents inexplicably allowed me to watch as a small child. That dragon is very reptilian and wild, pretty much the opposite of Smaug’s more refined intelligent evil.

These days I see dragons as demon-corrupted natural creatures. Start with a fish and you get a Tarrasque. Start with a crocodile and you get St. George’s dragon. They often combine elements from more than one animal, more chimaera than dinosaur. It makes them more distinctly supernatural and decidedly evil.

I have lots of different dragons, but the primary one is Maur, from Robin McKinley’s Hero and the Crown, because he was an immense foe even after his death.

For me, it’s the one on the Welsh flag. I had probably seen that image dozens of times before I ever heard the words ‘dragon’ or ‘draeg’.

There’s an interesting book called An Instinct For Dragons, which claims that dragons are a universal feature of human culture, including cultures in places such as the arctic that don’t have any snakes. The author postulates that the dragon is an instinctual archetype embedded in our neural hardware, and is a composite of three broad classes of predators which preyed on our early primate ancestors: four legged carnivores (like lions and leopards), winged raptors (like eagles), and venomous snakes. Dragons amalgamate our most primordial fears. No wonder they remain such potent and enduring symbols.

29: on size of dragons – interesting question.

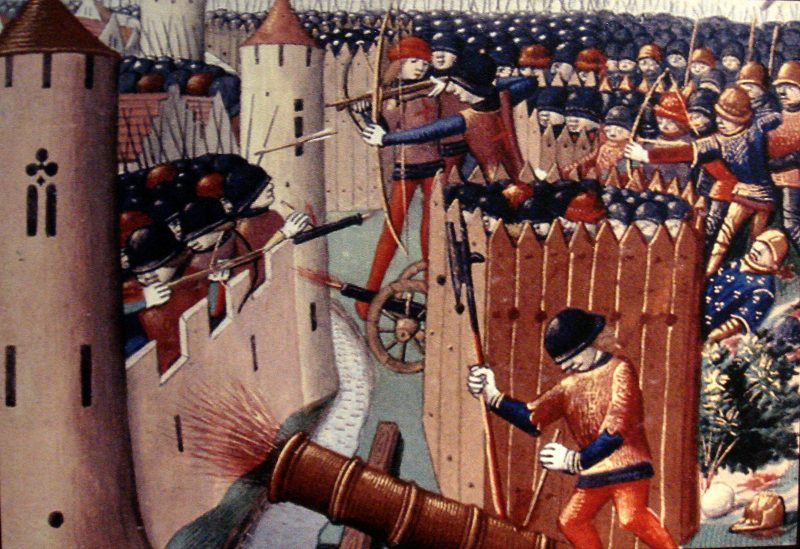

I would add that mediaeval artists were mainly concerned with fitting all the stuff into the picture that needed to go there, rather than making everything the right size in relation to everything else. This wasn’t helped by the fact that they hadn’t invented perspective yet. That’s how you get paintings like this  of the Siege of Orleans, in which you can clearly see that the moat around the city of Orleans was approximately 25 cm wide, and the city walls themselves were about waist-high. No need for scaling ladders, you could just vault over.

of the Siege of Orleans, in which you can clearly see that the moat around the city of Orleans was approximately 25 cm wide, and the city walls themselves were about waist-high. No need for scaling ladders, you could just vault over.

So even if a mediaeval artist had thought of a dragon being 20m long or 200m for that matter, he’d probably still have painted it horse-size, because he needed to fit St George (and his horse) in as well.

Smaug himself is not actually enormous, as Tolkien depicted him – if you compare him to the various bits of identifiable loot in his hoard, like swords and dwarf skulls, in “Conversation with Smaug” his head is probably about 2m long. That would make his body (including extremely long and slim tail) about 20m, very roughly.

In the film he’s at least six times this size.

I don’t think we can assume truly enormous size from the fact that Gandalf doesn’t think the Dwarves would be able to kill him. Gandalf does think that “a great Warrior, or a Hero” would be able to kill Smaug single-handed. The Dwarves are just not up to much when it comes to combat; they’re not soldiers, they’re exiled miners, and they’ve failed in every combat encounter they’ve had so far (the Spiders, the Trolls, the Wood Elves).

…and the Wargs, forgot to mention those. Really any adaptation that depicts the Dwarves as doughty warrior types with big axes is completely off track. Thorin’s party, with the possible exception of Thorin himself, are truly, irredeemably pants at fighting.

Vermithrax Pejorative is right up there, as someone else noted, and a close follow-on would be the dragons from the under appreciated 2002 film “Reign of Dragons”.

Oh, and yes, the dragon from Sleeping Beauty was the stuff of childhood nightmares, and a great stylistic rendition!

The covers of the UK editions of Anne McCaffrey’s books were beautifully illustrated by Steve Weston and his dragon artwork was so iconic that they are still the perfect dragon depictions for me. The first time I saw a US McCaffrey edition I felt quite distressed that the beautiful dragons of Pern that were wandering through my mind had been depicted as ugly monstrosities for those reading McCaffrey’s books elsewhere. I mean, how can anyone *not* want to depict the dragons in McCaffrey’s stories as perfectly beautiful creatures?

These are two of my favourite covers; I painted a version of the Dragondrums art as a mural on my bedroom wall as an 18 year old.

While I grew up with all of these (Pern, Smaug, et al), I just want to pipe up and say that Zubeia in THE DRAGON PRINCE (Netflix) is, to me, absolutely perfect.

Being Welsh, Y Draig Goch always lived in my head.

My first dragon image was the one I saw in a Chinese restaurant when I was a child. It was gold. After that it was Pern. The St George and the Dragon painting by Carlo Crivelli is one of my favorites. I had a poster from the ISG Museum of this hanging my work cube for years. A rather small and skinny dragon.

But my favorite is Julius Heartstriker from “Nice Dragons finish last” by Rachel Aaron. He was a blue feathered dragon. A grandson of Quetzalcóatl. In her books, the Chinese dragons had no wings but could fly .

I know and love most of these dragons, but the dragons in my heart include Temeraire and Laetificat and so many others in Naomi Novik’s books. Temeraire is a Celestial dragon, and comes closest to my mental image: huge, elegant, always learning.

I don’t have a particular dtagon in mind (though Pern’s dragons, as depicted by Michael Whelan, are closest as a class), but I found a TV “documentary” (narrated by Patrick Stewart here in the US) to encompass all of my mind’s pictures, from the prehistoric wyvern and a T-Rex fighting each other, to the more modern, four-legged dragons of recent vintage (attacking a mother-to-be dragon was not the smartest move those dudes made). A mockumentary I really enjoyed. (“Dragons: A Fantasy Made Real” in the US; “The Last Dragon” in the UK?)

So, yeah; more dinosaur-like, including being WARM-Blooded.

My first dragon image was Raphael’s from field trips to the National Gallery. Since then, for me, they’ve gotten bigger and become fire breathing. If I had to pick a single source, I’d say Smaug but with the temperament of Pern’s dragons (although I find riding dragons is wrong).

My favorite dragons are those from Pratchett’s Discworld which come in different breeds from huge to dog sized.

And don’t forget Asprin’s dragons.

An almost serious look at what real dragons might be (hydrogen powered): Flight of Dragons https://amzn.eu/d/2p6qGKo

I can happily report that I have always known dragons, and life is better for it!

My first dragons as a very small child were on the walls of a Chinese Noodle House in a small town: gold, sinewy, graceful and surrounded by clouds and fire. When I was a bit older I was taken to a performance of a dragon dance for Lunar New Year. That was the most magical, beautiful thing I could remember ever seeing. Later came the dragon on the Welsh flag on a cup brought home by a relative after a vacation. When I read the Earthsea Trilogy, the cover art by Pauline Ellison added depth and a sense of mystery to my conception of dragons. These things have informed my images of what a dragon looks like ever since. Graceful beyond measure, mysterious and grand, forever dancing in fiery clouds chasing the pearl of great wisdom. Gold and grey as mists in the morning.

The gas dragons from the very first Final Fantasy game still stick in my mind, and I Did Not Like Them.

Thank you for the illustration at the head of the article of a tile set by William de Morgan, a British Arts and Crafts artist who isn’t well known in the US (and probably even in Britain as a museum/library devoted to his work closed down this century). Mr. de Morgan visualized dragons in several ways (and dragon aficionados and Arts and Crafts aficionados) can see and even purchase tiles as places like Zazzle (just use them as decorative as one cannot be too sure of the inks).

Smaug and the dragons of Whelan are all well and good, but my first dragons were “The Reluctant Dragon” in book form with illustrations by Ernest Shephard and “The Dragons of Blueland” (My Father’s Dragon trilogy) I don’t know who did the illustrations for that, but those dragons were nice and they were, in modern terms “chonky”.

For my own writing, I imagine them in different sizes and I imagine them as their own very old civilization and no one would even *think* of riding one.

Another vote for the Welsh flag, as an image I saw regularly from childhood.

In fiction, I encountered Earthsea around the same time I first read The Hobbit, and it was Le Guin’s dragons that made the greater impression on me. I don’t think cover art played a huge part in forming my mental image. After all, you spend a lot longer reading the book than looking at the cover. (Well, I do anyway).

It also occurs to me that the drains of Earthsea are shape-shifters, in at least two instances: in ‘Tehanu’ and ‘The Other Wind’, the burned girl Therru/Tehanu turns out to be a dragon; and in the short story ‘The Rule of Names’, where the ineffectual village wizard, Mr Underhill, turns out to be the mighty dragon Yevaud.

(And I presume the name ‘Underhill’ is an intentional nod to Tolkien, as ‘Mr Underhill’ is Frodo’s alias when the hobbits arrive at Bree in the early part of ‘The Fellowship of the Ring’.)

In recent dragon stories, I’m currently enjoying Naomi Novik’s Temeraire series-–in audiobook version (which means I probably spend even less time contemplating the cover art).

For me, my first memories of dragons was the movie of Puff, the magic dragon. Later on, I got to know Falkor from the movie ‘the neverending story’, so only sweet and kind memories of dragons over here.

This came across my feed a week ago. I feel I know a little better what Tolkien had in mind with red/gold: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/jrr-tolkiens-estate-publishes-rare-lord-of-the-rings-paintings-and-maps-online-180979674/

@56 – In The Other Wind, the dragon Orm Irian takes the form of a young woman for her embassy to King Lebannen, and we learn that dragons and men were once one folk, the dragons having chosen freedom and immortality while men chose mastery, power, and rebirth.

One image that I haven’t seen mentioned in this thread is that of the dragon in the 1974 Fisher-Price Castle playset.

@60: The short story “Dragonfly,” in the anthology Tales from Earthsea, tells the first part of Irian’s story; she begins as a young woman, who subsequently transforms into a dragon.

@61. Faoladh: “One image that I haven’t seen mentioned in this thread is that of the dragon in the 1974 Fisher-Price Castle playset.”

Yes! Pink with blue trim, I believe… I thought of that almost immediately but didn’t share because it felt too much like an outlier to the conversation not being, I dunno, literary; same with the ceremonial dragon gear, red and gold, at Chinese New Year celebrations in our neighborhood that I recall someone else mentioning.

Another, very different example of a dragon: the Vietnamese-style dragon in human form in Aliette de Bodard’s In the Vanishers’ Palace.

EDIT: Yet another, again quite different: the dragons from the Middle Kingdoms series by Diane Duane – similar to conventional Western dragons in appearance, but immense, powerful, and with a back story that involves traveling through space from another solar system.

The animated film Flight of Dragons – inspired by Peter Dickinson’s illustrated book Flight of Dragons – informed my concept of dragons for much of my life. Along with a pseudo-scientific study of their physical properties, the characterizations brought to life by actors like James Gregory and Bob McFadden were charming and approachable, especially the eager, childlike Gorbash and wise, often-exasperated Smrgol. Dragon-shaped people. Smaug and the dragons of Earthsea continued to develop the idea of ancient, unknowable creatures inhabiting the mortal world yet still separate. We’re privileged to have such a wealth of lore and mystery.

My first image is certainly close to movies’ Smaug (even though I don’t actually think I ever watched them) or maybe DnD 5e’s red dragon is closer.

But, from my forays into web fiction, I acquired a deep fascination for unfathomably powerful and inhuman dragons. As the leading example there are the “dragons” from Demesne (on RoyalRoad) which are really roaming storms of wild magic that can do anything from transforming your house in iron, or wood, or, I don’t know, bone (concentrated amounts of transformed matter are refered to as dragon’s claws) to creating living or unliving abominations from nothing. They actually remind me of a description I heard about another work, which I can’t remember, that had dragons as bigger than mountains and less creatures than forces of nature.

Besides that, and much less dramatic, there is Paul Twister (unfortunately in indefinite hiatus as of the fourth book) where dragons are literal reality warpers, and the only one we meet is personally responsible for the separation between magic and technology.

And finally, the Paranoid Mage series has dragons as eldrich beings from another world, where they’re basically omnipotent, who occasionally send meatpuppets through. As an aside, these puppets are frequently reptilian and can spit fire, but that’s just because they think our stories are interesting, and they’re implied to be nothing like that in their own world.